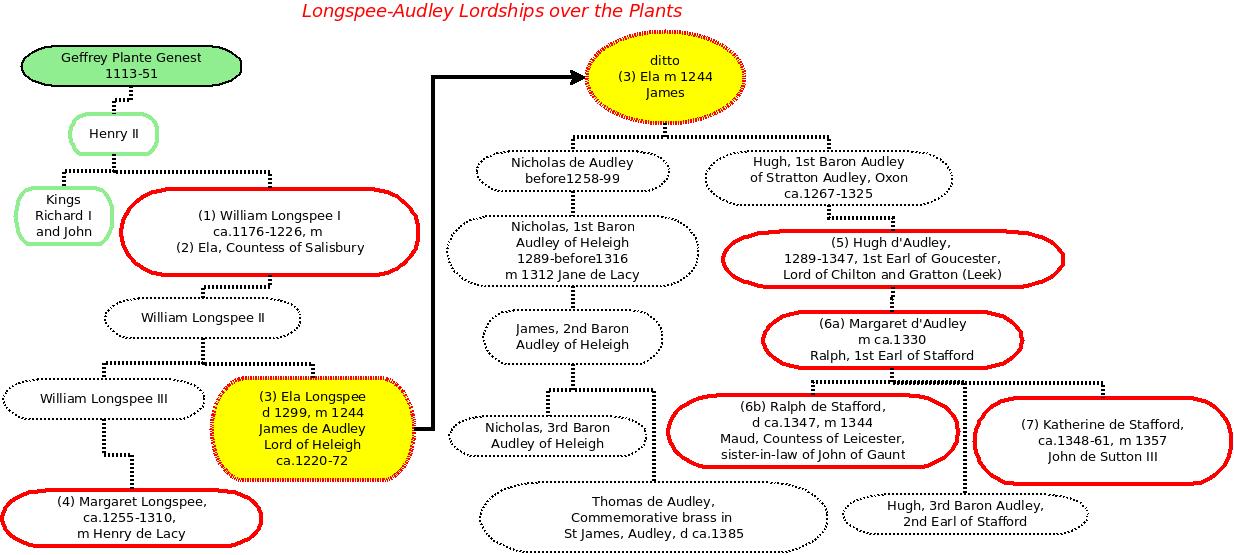

Introduction. This hypothesis is that the first Plants in England were followers or peasants under this noble Longspée-Audley authority. For this, the story begins a couple of generations earlier in France, with William Longspée's grandfather Geffrey, count of Anjou, who had been given the nickname Plante Genest (Plantagenet). Hence, the Plant surname might have followed some cultural tradition, accompanying the descent of the Longspées from their ancestor Geffrey Plantagenet. However, to avoid any misleading connotation for the name's meaning, it is important to emphasise the lower social status of the Plants beneath a line of descent from the great so-called Plantagenet dynasty. The known context of feudal links between Normandy and England, in connection with the early Plant name, are described more fully elsewhere on this website, where some other administrative links between early Plant locations are considered in more detail, especially for earlier times.

(a) Longspée - A grandson of Geffrey Plantagenet and natural son of Henry II, William Longspée (ca.1176-1226) was the forefather of a line of feudal Lords holding authority over the locations of the Plant name.

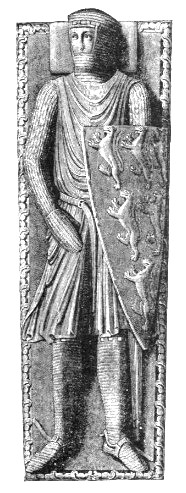

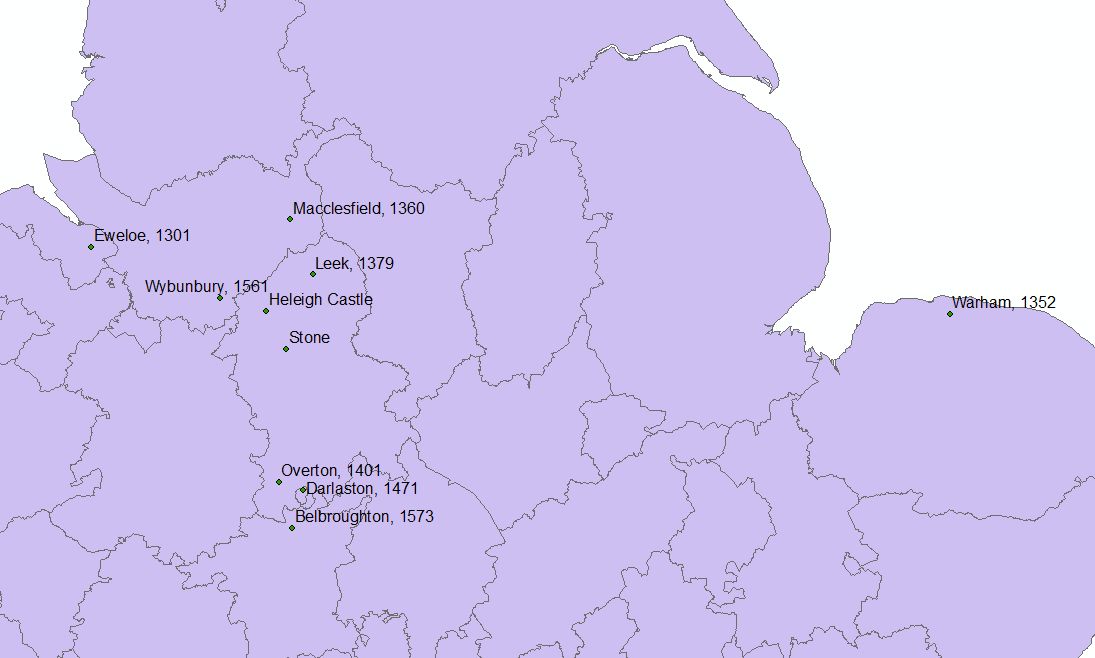

(b) Audley - Thomas d'Audley ca.1385 was a son of James, 2nd Baron Audley of Heleigh who in turn was a grandson of Ela Longspée (m.1244) and James Audley, Lord of Heleigh castle in north Staffordshire. The illustrated commemorative brass above is of Thomas in St James Church, Audley. This was at the time and place of the epic poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, reflecting noble competition, perhaps such as that between the king's heir's administrators of his palatine of Cheshire and Audley influence in north Staffordshire just across the county border. Though at least seven individual Plants are found in the Macclesfield Court Rolls in Cheshire in the 1370s, it seems likely that these were a minority of the Plants, evidently ones who had crossed the county boundary from the Audleys' Manor of Gratton (Leek) at the northern tip of Staffordshire. Amongst the local Plants, Thomas Plonte (page 4 of notes) was decreed an outlaw (1362-75), over the border in Cheshire, and he (or his namesake) was accused of aiding and abetting a murder at Leek (1379), along with the Abbot of Dieulacres who may have been 'policing' his north Stafforshire borderlands, though Thomas received the King's letters pardon and was released in 1382.

Abstract.

For the sake of presentation, rather than as a justification of the reasoning, the Longspée-Audley hypothesis is presented below in the reverse order of its inception: to wit, in chronological order. For this noble lordship over the late medieval Plant name, I include consideration of the context of a court with access to learned philosophy. A more general emphasis of life for a less learned local peasantry is given elsewhere on this website.Starting with an historic noble context for the word plant, which occurs as part of the royal name Plante Genest (Plantagenet) for example, we can consider the role of the vegetal or plant soul. A further finesse is that there was also a Platonic, as well as just an Aristotelian, understanding of the plant soul. Such early ideas likely accompanied the culture of the Longspée-Audley descendants of Geffrey Plante Genest.

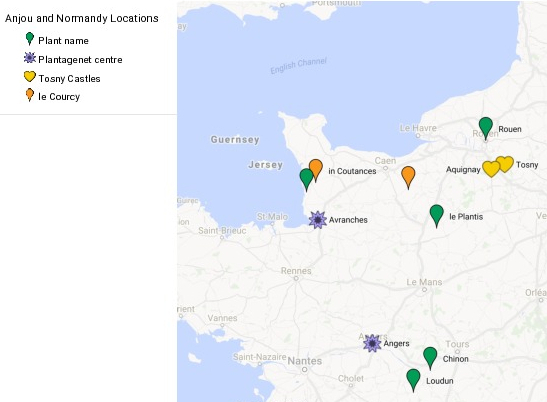

The Longspée-Audley hypothesis serves very well to explain the early distribution of the Plant surname in Normandy as well as through locations in England, as outlined towards the end of this webpage. The topic of context and meaning involves more lengthy discussion. By the same token however, this offers a fascinating and intriguing tale surrounding the development of early Plant-like names.

Instead of the name being coined in England, the Plant name could have been already attached to some followers of the Longspées from France. Alternatively a culture for the name could have been already ingrained in the parlance of the retinue of these noble lords who then ascribed such a name to their peasants. In particular, there was a noble Planta family of the Alps, with their name first known to appear in 46AD. Although it is unusual to consider that a name could have survived intact since that early, precisely that possibility has been claimed for the name Planta [G.R.de Beer (1952) Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, p.8]. Allowing a slight change in spelling, such as via Plante to Plant, an early origin would help to explain the abnormally large size of the main Plant family. Though few would believe that a single genetic family started as early as ancient or early medieval times, a less startling start in later medieval times could have allowed relatively prolonged family growth and an elevated chance of the main Plant family becoming abnormally large, as analyses based on DNA testing indicate it is.

In any event, life under the gradually diminishing fortunes of an illegitimate Plante Genest line of lords provides an interesting context for a changing sense to the Plant name. This does not pin down just one precise meaning for the Plant name. However, rather than seeking a single, simple, pithy meaning for the Plant name, in terms of modern English, the context of medieval times can add extra nuance to what the name might have meant to those who lived earlier. Though this is a relatively lengthy and somewhat burdensome task, it offers an advance on being tied solely to modern presumptions, perhaps misconceived, for this name which has been a topic of controversy not least concerning its inception.

Background to the development of this hypothesis

Though there has long been a conjecture that the Plant name related to the Plantagenet name, the hypothesis described here came about in an entirely different way. Rather than just wild speculation about some similarity of the names, it has transpired that the feudal lords presiding over the Plants appear to have been a particular illegitimate line that had earlier descended from Geffrey Plantagenet. Since the turn of the millennium, I have been accumulating early records for the Plant name, first through searches of the medieval Court Rolls held by the Keele University and, more recently, aided by the internet with such websites as The Original Record. This has led me (JSP) to replace the feudal hypothesis considered earlier, as outlined further elsewhere on this website, with the one outlined below.

For piecing together the hypothesis described here, it is first to be noted that there were particular proximities between the early Plant records and the noble Audley family of north Staffordshire. Upon examining the early marriages of the Audleys this brings in the Lacy family and especially the Longspée family and hence the locations of essentially all known early records for the Plant name in England. Moreover, William Longspée was an illegitimate half brother of both Richard Coeur de Lion and Richard's eldest sister Matilda who married Henry the Lion. This then extends a connecting hypothesis to the main locations of all early Plant-like names, further afield across Europe, suggesting how a fashion for ascribing such names to the peasants under this particular line of feudal lords could have developed.

By the times of the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the original grant of Normandy to Rollo in 911 (hatched area below) had been expanded to the west. William the Conqueror's route from Normandy is indicated by the mauve arrows in the map below. Normandy already reached as far west as the bishoprics of Bayeux, Coutances and Avranches; and, by 1100, the region of Maine also had been brought under Norman control, reaching southwards towards Anjou.

After the Historical Atlas of the Medieval World,

(Penguin Books, 2005), page 47.Count Fulk of Anjou became king of Jerusalem through marriage in 1129. This left Anjou to his son Geffrey (1113-51) who, at the age of 15 in 1128, had married Maud (1102-67), the widowed Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. In particular, Maud was the heiress to the English throne. However, upon the death of her father in 1135, her cousin Stephen claimed it leading to the so-called English Anarchy.

Count Geffrey of Anjou claimed back Maud's inheritance of Normandy, becoming duke there in 1144, while she and their son, Henry FitzEmpress (1133-89), fought Stephen in England. Eventually, in the 1153 Treaty of Winchester, it was agreed that Henry FitzEmpress should succeed after Stephen's death to become Henry II of England, as indeed happened in 1154.

The Jersey born poet Wace (ca.1110-after1174), who became Canon of Bayeaux, referred to Plante Genest in a poem. The Angevin monk John de Marmoutier attached this nickname Plantegenest more explicitly to Geffrey, in an account of the Life of Geffrey – a work which around 1170 he dedicated to Geffrey's son Henry, who had by then become king of England.

Seal of Henry II of EnglandHenry FitzEmpress (1133-89) had earlier become duke of Normandy from the age of 17. He inherited Anjou in 1151 and married Eleanor of Aquitaine the following year. Eleanor had inherited her father's Aquitanian estates in 1137. She had crusaded with her first husband, the king of France, but her first marriage (1137-52) was annulled on the grounds of consanguinity in the March of 1152. She married Henry in the May of that same year before he became king in 1154.

Henry II's wife Eleanor of AquitaineIn the map below, the brown areas were inherited by Henry from his father Geffrey Plantagenet (Normandy, Maine, Anjou) and his mother (England and south Wales). He acquired the purple area through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. He also acquired Brittany (dark green) and much of eastern Ireland by conquest and diplomancy; with the rest of Ireland, Wales and Scotland recognising him as their overlord. He also claimed the County of Touluse (orange). The map below represents his so-called Angevin Empire at its height stretching from the border of Scotland to Castile, Navarre and Aragon (now all parts of Spain) to the south.

After the Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, (Penguin Books, 2005), page 51.This Angevin Empire subsequently collapsed through the campaigns (green arrows) in 1202-4 of king Phillip II of France and his allies. Subsequently the counter offences by Henry II's youngest son King John in 1214 (orange arrows) retained the hatched area in Aquitaine whilst the loss of continental lands especially to the north was affirmed with further campaigns (deep purple arrows), in 1214, by Phillip.

In the intervening years before this collapse, Henry's son and successor to the throne (1189-99), had been Richard Coeur de Lion (Lionheart), who had links to the Pyrenees through his mother Eleanor and his wife Berangeria of Navarre and also to the Alps through his eldest sister Matilda who married Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony and Bavaria.

Henry and Eleanor's children Matilda and Richard with Louis of France at Palermo in 1190Richard's wedding to Berangeria took place in Sicily in 1190 while he was on his way to leading the Third Crusade. The marriage was promoted by Richard's mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, in league with Berangeria's father, Sancho VI of Navarre, as part of an alliance to protect Aquitaine's southern borders, especially while Richard was on Crusade. This illustrates a possible feudal context for Plant-like names in SW France, near the Pyrenees, though the earliest occurrence of these names is unknown, apart from the rather different name Bernard Plantapilosa of Aquitaine (ca.870).

Richard's eldest sister, Matilda (1156-89) was apparently she who was obliquely revered as Elena or Lana in two courtly love poems by the troubadour Betram de Born. She married Henry the Lion in 1167 who was at that time a close ally of Frederick I, the Holy Roman Emperor. Henry's first wife (1147-62) had been Clementia of Zahringen, a great granddaughter of Clementia of Aquitaine (1060-1142) whose children had featured severally in the First Crusade (1096-99). In 1147 Henry the Lion had taken part in the Second Crusade and later made a pilgrimage to the Holy Lands in 1172 while Matilda governed his vast estates in Germany.

The late medieval name Plant, especially in Normandy

The name Planta, von Planta, or de la Planta, is found severally in the Alps, in 46AD and at least since 1244, especially near the German speaking Engadine which means, in Romansh, garden source of the River Inn. The River Inn flows from the Alps into Bavaria where Henry the Lion, the husband of Henry II's eldest daughter, had been duke.

It is unclear whether the name de la Planta was brought back from the Alps to Anjou or Normandy around 1182 or 1194. In 1192-4, on his return from the Third Crusade (1189-92), Richard the Lionheart had been held captive near the Alps in the Kingdom of Germany (within the Holy Roman Empire). Here, the Lionheart's brother-in-law, Henry the Lion, had been duke of Saxony (1142-80) and duke of Bavaria (1156-80) but he and his wife Matilda had been forced to flee into exile at the court of her father, Henry II, in Normandy in 1182 where they were shown 'sumptuous hospitality and royal generosity' for three years.

In 1202, a landholder called Eimeric de la Planta near Anjou was killed or captured or somehow dispossessed of land following John's short-lived victory there at the battle of Mirebeau. Eimeric's name is recorded as de Plant', aswell as de la Planta, presumably just an abbreviation. One possible meaning of de la Planta might have been 'from the Engadine'. Either way, such a meaning could have been forgotten at this distance from the Alps. Some time after the Lion's exile to NW Europe in 1182, there are references to other places with similar names.

Other associations with place names arise with Rad de Planteiz (1198) near the village of le Plantis in Lower Normandy and, nearly a century later, there is a William de Planty (1271) holding land at a village called Planty south of Paris. There are also the names de la Plaunt and Plaunt, in 1273, for three Rouen merchants in Upper Normandy.

The use of the de prefix provides ample evidence that the word plante (or similar) was severally associated with a locative origin (perhaps referencing a 'planted place'). This is not the whole story however. In 1180, before the Lion was forced into Normandy in exile, there had been the name Durand Plante in the region of Coutances (see Normady map above). Also, at some time during the Lionheart's reign (1189-99), there is the name Ranulph Plantul also in Lower Normandy. The word plantul means a seedling or young shoot and the word plante could often have this same meaning at that time.

Around the same time (ca.1180), there is the name William Plantapeluda meaning 'hairy shoot', in connection with a priory in Dorset in England for which the mother house was Montebourg Abbey in the region of Coutances. This might have been inspired by some commonality of meaning with the contemporary (ca.1170-80) noble name Plantegenest meaning 'sprig of broom', which is hairy. This would have been a revival of meaning however since the name Bernard Plantapilosa, also meaning 'hairy shoot', had occurred much earlier in connection with Aquitaine in the ninth century.

Modern misconceptions of meaning

The meaning of the word plant has changed substantially with scientific advance. Plant is now a primary word in botany. Early usage was often very different. For example, early texts refer to establishing (planting) an orchard [OED v 1a] or a religion [OED v 2a] or instilling ideas [OED v 3a]; also plant [OED n1 1(b)] could mean a young person planted and springing up (OED = Oxford English Dictionary, 2015 edition).

A controversy has persisted for centuries concerning the origins of the Plant name. Many have accepted the meaning gardener, though almost all known occupations of the early Plants are very different. Some have proffered more erudite meanings, typically dismissed by those less interested. One might resign to Bardsley's candour on Plant:

"I give this up. I can suggest no satisfactory solution". [A Dictionary of English and Welsh Surnames, written: 1872-1896 by Charles Wareing Endell Bardsley].However, a few words on medieval scholastism can be ventured to help tie together the now obscure early senses.Scientific classification of the life forms took hold especially with Linnaeus (1707-78). Thereto, the scholastic rationalisations of Grosseteste (b ca.1175) had remained in common parlance prior to the developments of modern Physics and Chemistry. This medieval scholasticism, which was beginning to incorporate the teachings of Aristotle, involved the many forms of light besides God's light as implanted in particular in the vegetable soul. This plant soul underlay the life forms being in animals as well as man, as had been taught earlier by Avicenna (b ca.980) in the Middle East. However, Aristotelian teachings were still being denied in Western Europe throughout the thirteenth century. More generally, life giving light was consistent with the teachings of Avicebron (b 1020) concerning emanations from matter like a Flow of Light or a River of Life (such metaphors as these are used in such works as Avicebron's Fons Vitae, meaning the Fountain of Life).

Scholastic accounts of the vegetative soul...

Robert Grossetest, b ca.1175

St Thomas Aquinas, b 1225Saint Thomas Aquinas (b 1225), incorporated ideas of The Philosopher (essentially Aristotle b 384BC) into Christian teachings and associated three powers of the soul with a vegetative soul, arguing that its generative power was more noble than its nutritive and augmentative functions. Hence we can surmise that, from around those times, the vegetative soul was the foundation of life like the sole of the foot or the source of a river or the light of the Word of the Lord.

There is evidence for the following early known meanings of the word plant in English:

- to instil or implant [e.g. OED v 3a]: there are early references to planting virtue, contrition, the grace of noble lineage, the Lord's Word. This directly gives a clear sense to the medieval by-name Plantefolie, with the consistent spelling folie or folye, since folie means foolishness or wickedness in both Anglo-Norman and Middle English: hence, an instiller of foolishness or wickedness, apparently most obviously a jester, though perhaps a leaf or tree planter if we allow a very different spelling such as feuille. Similarly, in a courtly context, Planterose means an instiller of romantic life spirits while Plantefene means one who instils life eagerly (not the different Latin word faenum meaning corn) and Plantebene means one who instils well (not necessarily beans).

- the word planted could mean established: an important primary source for Middle English is the author of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (associated with the late fourteenth century main Plant homeland) whose works include such phrases as that Wyz that all the world planted [Patience 111]. The word Wyz is difficult but could well refer to God with also some possible resonance with a crusader such as the Lionheart or Longspée. The meaning to establish is also apparent earlier in Old English [OED v 2a].

- young person: as a thing springing up, this is attested in English from 1393 [OED n1 1b] though not unequivically as a person, according to the OED, until 1685. Others, however, attribute this meaning to much earlier, as evidenced for Old Welsh and British Celtic and with a Latin meaning scion (there is a suggested etymology planta -> clanda -> clan though more specifically -> plant meaning children in modern Welsh). There is also such usage for plant in early modern Cheshire.

- sole of foot [OED n2]: attested in English from 1382, in Old French (plante) from 1150, Spanish (planta) from 1200 and Italian (pianta) from 1292.

Some early Name Instances

The first known instance of the 'Plant' name was for Julius Planta, a friend and advisor of the Roman Emperor Claudius. He was granted judicial rights at Trento (near the Alps in northern Italy) allowing such meanings as the classical Latin meaning scion (a young emergence of life) perhaps as a noble child, or as a source of living authority (the metaphor of a 'source of life' was locally available in so far as the source of the River Adige is just across the Italian watershed from the Inn Valley as it leaves the modern Swiss county of Engadine). The heraldry for the noble Planta family in the Engadine, attested much later, is a severed leg of a bear showing prominently the sole of its foot (perhaps alluding to an earlier severed sole in the sense of a foundation of authority, dating from Roman pre-Christian times).

The Roman Emperor

Claudius was a

friend of Julius Planta (46AD).A millennium and more later, a connection with medieval Plant-like names occurs with Ida de Tosnay who was a ward and mistress of Henry II, by which came William Longspée (b ca.1176) with whose descent the English Plant surname is here associated, as substantiated later below. Ida then married Roger Bigod whose grandson Roger, a ward (1225-26) and nephew of William Longspée, had a butler Roger Plantyn (1254, 1258) with lands in Norfolk. The name Plantyn could be a diminutive meaning something like a little pageboy or perhaps an establisher or founder, as coined by the Bigod earl of Norfolk (cf. the contemporary Norfolk record for Roger Planteng' in 1268).

Geffrey Plante Genest

was Count of Anjou

where Eimeric de la

Planta lost land

in 1202.

Geffrey's grandson

William Longspée

was an illegitimate

son of Henry II and

Ida de Tosny.

The Plants are found near

this Longspée line. Ida

was also the grandmother

of an earl Roger Bigod

whose butler was called

Roger Plantyn (1254, 1258).Ida de Tosnay was from a noble family with castles in 1119 at Tosny, Conche, Portes and Acquigny in Normandy, having 50 or 51 knights fiefs, as well as scattered lands there in 1176. Following the defeat of king John and Roger de Tosny in 1203, they reputedly withdrew to England though English trade continued with Rouen (near Tosny) where, in 1275, there were three merchants called de la Plaunt and Plaunt. In Normandy, there is also mention of the manoir of le Plantis in a 17th century book and a village called Plantis still exists in Normandy. Plantis is Latin genitive plural, meaning of the Plants, perhaps alluding to plantings of sole, soul, vines, gardens, or orchards; or relating back to a place perhaps even as far away as the Engadine; or possibly even to any place thought to be instilled with plant life or the Lord's emanations.

Documented medieval beliefs

In the Normandy Rolls, the name de la Planta appears in 1202, also written de Plant'. In Normandy, it reappears as de la Plaunt and Plaunt and, in England, as Plauntes and de Plantes though more commonly Plonte, Plante and Plant. Pragmatically, this suggests that this is a locative name with a meaning such as from the Engadine or from le Plantis. For de Plantes, there is also the Aristotelian work De Plantis, in which plants have a soul suggesting an influence of a faith based on a classical philosophy. Late medieval times are typically described as an Age of Faith with both crusades and pilgrimages to the Holy Lands, including Damascus. The Aristotelian work De Plantis is now, since 1923, attributeded to Nicholaus of Damascus - in his autobiography, he wrote that he wanted to retire in 4BC but was persuaded to travel to Rome and it is shortly after, in 46AD, that Julius Planta is recorded as a friend and advisor of the Roman Emperor, at Trento near the Engadine.

Here, in this Germanic region of the Alps, the etymology of the word soul is said to be the proto-Germanic saiwalo meaning lake or sea, as an origin and departure of life. The chain of lakes in the upper Engadine valley could have been seen as a foundation of such a watery soul, as well as a source for a River of Life. In classical Latin, planta means a young shoot (attested back to at least 1292 in Anglo-Norman and 1149 in Occitan) or sole of foot (attested back to ca.1150 in Anglo-Norman and at least ca.1200 in Spanish). We can summarise that an initial meaning for Plant, in late medieval times, could have been from the Engadine (a source of soul and vegetative plant life) which, under a feudal Lord, when assimilated into Normandy and England, could have become a basic soul to be instilled with the Word of the Lord.

The above meaning is consistent with the teachings in England of Roberte Grosseteste (ca.1175-1253) and Roger Bacon (ca.1214-19). Later, Geoffrey Chaucer (ca.1345-1400) wrote about planting the root of youth in the eyres of the first father that his growing be in vertue like a godenes...

The first father in majesty that makes [for] him eyres ... Plante the rote of youghthe in such awyse That in vertue your growyng be alway Loke ay godenes.

Extract from The lyfe so short and the craft so lo[n]ge to lerne. Though the first father is typically taken to refer to God, there was also some consistency with a possible parallel allusion to the first father Plante Genest of Chaucer's master John of Gaunt. Vertue can mean semblance and, in Gascon, to plant means to feign (cf. reproducing the Father as a child or feigning an offspring of an Old Aquitanian deity such as a flower).Chaucer was a friend and servant of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, who had supported John Wycliff who was condemned by the Pope for his views on the transubstantation of bread (and wine) into both the body and spirit of Christ. Around the same time, there is north Staffordshire mention of levened flour and rose reflair (perhaps spirit arising as a scent) in the writings attributed to the so-called Gawain poet of the main Plant homeland. These writings mention how we leven on Mary as a grace of grewe that bore a child from virgyn flour [Patience 425-6] and, after birth, there was rose reflayr where rotz had been ever [Cleanness 1079]. The Gawain poet also wrote of baptismal compassion (a tear) for a pagan corpse dressed as a king which turned its flesh to dust and sent its soule to blisse (heaven) [St Erkenwald 266-7].

The foregoing section might seem complicated but the complication is mainly modern science and the need to deconstruct modern beliefs. It seems that for a medieval mind, much of it was very simple: life needs plants and plants need light and water.

In a Classical period text ascribed to Empedocles (490-430BC), the Greek goddess Persepone is apparently associated with the classical element water and hence the name Nestis. This goddess of vegetation and the underworld becomes Proserpina in Roman mythology derived from proserpere meaning to shoot forth. Cicero (106-43BC) calls her the seed of the fruits of the field and Plutarch (46-120AD) identifies her with spring.

The goddess of vegetation and the underworld...

[The Greek goddess Persephone (Heraklion Museum, Crete)

and her Roman counterpart Proserpine (1873-77 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti).]Water seems to have been an important element particularly in northern Europe whilst light was more to the fore in the teachings of St Augustine of Hippo (354-430AD) in the south. Either way, water and light came together in plants.

The next question is: do we need to elaborate on this or just leave the Plant name to mean a basic soul? We could consider help from the name Plantefene, for example, which could have meant, at least to a learned scribe, a planter of eagerness or an eager soul, rather than a planter of corn. For Plantagenet (originally spelled Plante Genest), there appears to be an emphasis on the generative power [Plant, 2007], hence the hereditary (genetic) aspect of a plant (the word gene long predates DNA). For Plant pure and simple, we have no clue other than searching for the original, or contemporary, context of this surname for which the main Plant homeland of Staffordshire becomes especially relevant by late medieval times.

The Planta name in the Engadine

In the Engadine of the Alps, we have a pre-Christian context and the waters of the Engadine, for a noble Julius Planta (ca.46AD). We also have the contemporary teachings in De Plantis. Earlier Aristotle (384-322BC) in On the Soul (402a) had judged that plants had the capacity for nourishment and reproduction, the minimum that must be possessed by any living organism. More contemporaneously with Julius Planta (46AD), Nicholas of Damascus is believed to have written De Plantis (815a), though this has come down to us through an unknown history as far as a surviving text by a thirteenth-century Englishman called Alfredus.

De Plantis is regarded as a pseudo-Aristotlean work. However, even as late as late medieval (so-called Plantagenet) times, John of Gaunt's associate Wycliffe ranked Democritus, Plato, Augustine and Grosseteste above Aristotle. De Plantis begins by dismissing the first two of these philosophers but, as will be explained, it seems especially relevant here to consider that Wycliffe, rather than dismissing them, highly rated these two philosophers, Democritus and Plato, and this might hold relevance in connection with the Plantagenet name of Gaunt's ancestor, aswell as for a contemporary meaning of Plant.

The fact that, in his De Plantis translation, Alfredus dismissed such philosophers as Democritus and Plato, despite the fact that they were preferred by Gaunt and Wycliffe, can be taken to suggest that a variety of beliefs were still in contention around the times of surname formation.

De Plantis starts by noting that life is found in animals and plants though it is more hidden in the latter. It summarises the views of some other Greek philosophers, such as Plato (ca.425-348BC) who says that whatsoever takes food desires food, and feels pleasure in saiety and pain when it is hungry and that these dispositions do not occur without the accompaniment of sensation. It adds that this view of plants, having the sensation and pain, is marvellous enough; but, Anaxagoras (ca.500-428BC) and Democritus (ca.460-370BC) and Empedocles (ca.490-430BC) declared that plants possessed intellect and intelligence. Though the writer of De Plantis repudiates this, stating that nutrition is merely the cause of growth in the living thing, the introduction of De Plantis makes it clear that there remained an understanding of an alternative view, which ascribed more than just an insentient soul to plants: plants could indeed feel and understand things. Such beliefs evidently remained relevant in late medieval times, when the Plant surname is found near an illegitimate Plantagenet line.

Arrival of some similar notions in medieval England

The times of the thirteenth-century arrival of the Plant name in England, following a known instance of the Plante name in late twelfth-century Normandy, was at a juncture of philosophical change. The teachings of the ancient philosophers (including those cited near the beginning of De Plantis) were receiving renewed prominence at the times of the developing Plant name.

For example in that context, perhaps oddly to modern minds, the vegetative soul was sentient and felt pain.

Also, in pre-Christian times around the inception of De Plantis, there had been the idea of goodness illuminating the intelligible with truth, just as the sun bestows light. For example, Socrates (ca.470-399BC) had revealed the child of goodness to be the sun, bestowing the ability to see and be seen by the eye.

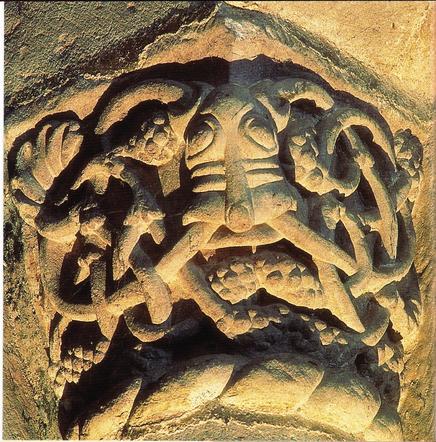

Thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Green Man Heads coincide with scholasticism's peak in popularity, with more aspects of Greek philosophy entering Christian teachings at that time, and such rediscovered ideas found their way, it seems, onto the faces of some Green Man Heads.

The vegetative in pain; also, uttering to the eye...

[Green Man heads at Tewkesbury and Bolton Abbeys from Mike Harding (1998)

A Little Book of the Green Man ISBN 978 1 85410 563 9.]Some notes on Green Man Heads. In medieval art and architecture, Green Man Heads were popular images in European churches from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, that is during times that coincide with so-called scholasticism, which combined christian teachings with ancient Greek philosophies. Scholasticism reached its peak popularity in the thriteenth and fourteenth centuries and this coincided with more naturalistic Green Man heads in place of ugly masks, monsters and demons, which are found more often in surrounding times, both a century before and after. An underlying style of art first appeared in illustrated written works in the tenth century, developing especially in northern France in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, where such designs generally provided a border of tangled branches or vines, not unlike the tangled serpents of earlier Celtic and Saxon art, with one serpent often biting its own tail or that of another. Green Man Head embellishments of Romanesque architecture (which is usually called Norman architecture in England) made their way into churches in the twelfth century in a souless form, before developing with the finer art of Gothic architecture. The example to the left below (at Langdon Church in Staffordshire) shows a twelfth-century mask spewing branched foliage and it can be compared with the more naturalistic fourteenth-century examples to the right (at Much Marcle in Herefordshire and at Finedon in Northamptonshire).

[Development of Green Men Heads from Normandy in medieval England,

.jpg)

.jpg)

from Richard Hayman (Shire Publications Ltd, 2010) The Green Man ISBN 13:978 0 74780 784 1.]Some aspects of medieval philosophy are outlined here and add some context to the philosophical development of the vegetative soul.

Even by the tenth-century in northern Italy, grass turves were being worshipped as embodying generative powers [perhaps with the soil of the turves being seen rather like the liver, in this case as a source through roots to the grass]. Atto of Vercelli (924-61AD) complained in a sermon of the custom, practised by `little trollops' (meretriculae) in his diocese, of baptising branches and turves, calling them co-parents and hanging them in their houses, afterwards guarding them assiduously quasi religionis causa.

This had hence continued to ascribe human characteristics to vegetable matter - in this case, it ascribes the generative (parenting) power of Plato's appetitive soul to branches and turves. The Aristotelian generative power of the vegetative soul, along with its nutritive and augmentative powers, became more orthodox through the scholasticism of St Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) and others. Exceptionally, the Aristotelian powers of the vegetative soul had been mentioned earlier by the Latin Church father, St Augustine of Hippo (354-430AD).[De Libero Arbitrio, I.8] Hence, this particular teaching of Aristotle might have been considered as less heretical than some of his others, albeit rather at odds with Plato's more sentient vegetal soul, with both versions likely to have been in contention around the times of the thirteenth century.

Personification of virtues while approaching the nutritive and generative...

[Shame, the daughter of Reason, leads the young lover into the Garden of Delight, which Genius likens to the (Heavenly) Park, flowing with the nutritive and generative Fountain of Life. (Roman de la Rose, 1230-5 and ca.1275-80AD)]

Modern times in the Aquitaine

Though less well dated, we also have Plant-like names in SW France (Plante, Plantie) associated with the region called Aquitaine. The English chronicler, Ralph de Diceto (d ca.1202), wrote of the Aquitaine, From the Pyrenees northwards the whole countryside is irrigated by the River Garonne and other streams, indeed it is from these life-giving waters that the province takes its name. Rather similarly to the Engadine, the main headwaters in the Pyrenees of the Garonne is a lake (called Saboredo). Life giving waters (cf. the Germanic soul) are hence clearly in evidence in both places.

An old dialect (Lange D'Oc) has been associated with the Aquitaine and the upbringing there of such nobles as Richard Coeur de Lion. More generally for southern France, where documentation is not good, Dr S-J Honmorat published a dialect Dictionary in 1881, which he called Provencale French or, as an alternative title: Langue D'Oc, old and modern, based on a Provencale vocabulary. In this, he listed a number of plant-based words (plant-agi, plant-ada, plant-aire ...), gave much the usual medieval meanings for plante/planta/plant, and listed three phrases to illustrate the word's usage including una bella planta d'homme which he said meant a handsome sprig of a man, hence an ironical term for a small man. Though this has never been considered seriously for the English surname Plant, to the best of my knowledge, we can consider some possible circumstantial ideas.

Metaphors and beliefs and specific interpretations

It is generally agreed throughout European Language Dictionaries that, in medieval times, plant was more likely to mean a small shoot or tree than is now the case. Also, in support of the Aquitaine, developing DNA evidence indicates that the male-line ancestors of the main Plant family were likely to have been in SW France around 4,000 years ago, though of course a lot could have happened before the surname came about in England. Strabo (64BC-ca.24AD) noted the Aquitanians had bodies more like the Iberians than the Gauls though average heights in France and Spain now differ little. The first Plants in England were not necessarily the famed Gascon crossbowmen from that region of around 800 years ago. Nor can we be sure of the first Plants' sizes. However, a nickname based on the plant sense sprig, to mean small or short, is a quick and simple image metaphor. This is much like the English surname Twigg which is said to mean a thin person.

The danger is that we fall for the classic availability error whereby we prefer a timeless metaphor to the well documented deeply-held beliefs of early times. Though adopting the former is much easier than having to re-adjust our mindset to medieval times, that does not mean that the easy option was initially the most salient meaning.

There are other elaborations on a basic soul besides a small man, such as a child ready for instruction. It might also be relevant that this 1881 Dictionary was written after the French Revolution which itself might have had an influence on attitudes towards the noblity besides a likely view that the Plantagent kings had become the foes of France. Geffrey Plante Genest is said in modern times to have had two nicknames - the handsome as well as sprig of broom - and this 1881 phrase, a handsome sprig, albeit likely amusing to many, could be seen as a concoction that neglects earlier beliefs and adds a particular geo-political viewpoint. Indeed, a core meaning basic soul for Plant seems to have been elaborated variously. Those with different standpoints and opinions have developed this basic meaning in various ways. For example, those mindful of tamed nature in post-war suburbs have favoured, of late: a gardener.

Towards sense in an Anglo-Norman context

More contemporaneously with late medieval times, Alexandar Nequam (1157-1215) was raised as a foster-brother of Richard the Lionheart and, in his work De naturis rerum (ca.1190), he wrote of the moral qualities of plants and animals. The Middle English herbal Agnus Castus gives more detail of the specific moral and medicinal qualities of particular plants (such as broom). In a more legalistic record, the Macclesfield Court Rolls mention Richard Plont in close association with Nicholas le Gardiner (1401). It can be considered that it seems unlikely that both names had originated in the same place with the same meaning gardener. It is not impossible that such occupations as herbalist and gardener were around. In this specific record, Plont is a guarantor of le Gardiner for the farm of deadwood and coal.

Whether from the Engadine or from Aquitaine, the main 14th century homeland became the relevant context for most English Plants. As a part of this local context, the arriving foreign nobility were relevant since the feudal Lords held power over the scribes who wrote the surviving records for the first known Plants; the Church aristocracy also held influence. In particular however, the heir to the throne held particular influence in Cheshire. Feudal influence that descended from Henry II also held sway immediately to Cheshire's south, with the illegitimate Longspée-Audley line within particular parts of the county of Staffordshire.

Plantings of the Lord's emanations...

A crusader supplicates the Lord for His Light with belief in the creative powers of emanations (cf. Grosseteste)

A surviving inscription beseeching such a planting: Here Doe O Lord Svre Plant Thy Word - Wincle Chapel - in the main Plant homeland

English Surname theory

There is a modern view concerning English surnames that we should move on from quick and easy meanings that apply universally in every conceivable context. Surname Dictionary meanings are aimed at providing a single pithy meaning for each and every surname, as arrived at circularly from generalisations about surname meanings. For his influential 1958 Dictionary of English surnames, P.H.Reaney wrote `many surnames, previously regarded as nicknames difficult to explain are really occupational'. This is the basis on which Reaney asserted that Plant was a metonym for a gardener. However, Prof Peter McClure in a 2013 article [Explaining English Surnames: linguistic ambiguity and the importance of context, Nomina, 36, pp.1-34, esp p.18] cited Reaney's statement, allocating a pervasive occupational class to awkward nicknames, and commented that it lacks attention to other possibilities.

Semantic ambiguity is pertinent for Plant, especially in its medieval context when the meanings of the word plant were typically very different from now. In particular, there are also socio-political extremes ranging from a vulgar base soul, with its power of reproduction, to the name of the forefather of a famous line of medieval English kings. Similarly, there were medieval Christianity's concerns over original sin, disecting love into its carnal and divine forms, with such medieval phrases as lufe norrysches the plantes of all vyce and pull up thornes of vicis for to plaunte vertues. Seeking further clues to the Plant name's origins and initial meaning remains relevant if we are to progress beyond a meaning basic soul.

Anjou and Normandy

As well as power and politics near the Alps and Pyrenees, the more local feudal authority in England needs to be considered. Currently, the DNA evidence for the male-line ancestors of the main Plant family is evolving slowly. So far, this suggests little more than this Plant family's ancestral line could have arrived in England via northern France within the past few milliennia. So far, only hints of help for the deep ancestry are available. As well as several others, the Y-DNA is showing a deep genetic connection to someone called Coursey for example -- the village of le Plantis is not far from a place called le Courcy in Calvados and by 1180 a Durand Plante was in Coutances near another le Courcy there in Basse Normandy.

In recorded history, we might consider the outset of the English Anarachy in 1135. Geffrey Plante Genest took his Angevin army to Sées in the Normandy department of Orne (previously part of the province of Perche), just 9 miles from le Plantis which is also in Orne. The historian Orderic Vitalis (1075-ca.1142) details Geffrey's subsequent withdrawal from Sées stating his army dispersed through the province round about [Sées], committed outrages, violated churches and cemeteries, oppressed their peasants, and repaid those who had received them kindly with many injuries and wrongs. It was in a subsequent campaign of 1142-43 that the Avranchin and Cotentin, in the west of Normandy (adjoining Brittany), surrendered to Geffrey. After the murder in 1170 of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Geffrey's son king Henry II eventually paid penance at Avranches in 1172.

The Spanish historian Martin Aurell (2007) cites Wace's mention (ca.1160-70) of the name Plante Genest for Geffrey and relates it to the foundation of a hunting area rather than to Celtic mythology. He does not mention the geographical situation at Avranches, close to Wace's Jersey origins and Wace's evident appointment as Canon of Bayeux.

It is claimed that the placename Genêts near Avranches, at the mouths of the rivers Sée and Sélun, comes from the Celtic (Breton) word for mouth. This suggests a possible connection here to the outflow of a river's watery soul; the origins of the name Plante Genest could thence highlight generation through plant life, such as near Genêts. There was specifically the contemporary belief in the generative power of the vegetable soul, as appropriate to the writings of a Canon. In particular at Genêts, we might think of the generative forces of competing river flows, which shift the river courses through the sands near Mont-St-Michael. Though Wace does not mention it by name, there is a possibility that Genêts had a special significance for Geffrey's receipt of his nickname. John of Marmoutier wrote (ca.1170) that Geffrey had taken the side of the minority Bretons (ca.1131), to even the odds in a fight with the Normans, in sight of Mont-St-Micheal (i.e. at or near Genêts) and, following victory in battle, he had gone on personally to defeat and behead a giant Anglo Saxon in single combat. Similarly to a power of generation, the specific OED senses of founding and establishing seem relevant to Geffrey, as well as his generative fathering of royal life (Henry FitzEmpress, later Henry II, had been conceived the next year in 1132). However, it is of course clear that a sense of militaristic foundation does not apply equally to the Plant surname — in 1180, Durand Plante had some of his chattels confiscated for fighting duel upon duel, perhaps suggesting that he did not have permission to duel as a means of trial by ordeal.

The vegetative plant in Staffordshire

Shortly after the first known mention (ca.1160-70) of the Plante-Genest nickname of Henry II's father, in Normandy and Anjou, an illegitimate line of descent from Henry arrived in Staffordshire. This arose from a union of the Angevin and Tosny noble families which begat William Longspée who is known to have been holding the castle of Pontorson (near Genêts) in 1198 and again in 1203. The Plant name, if not the Plants themselves, can hence be considered to have passed from Anjou through Normandy with the Longspée descendants who then ruled locally over almost all of the known Plant records that occur throughout medieval England.

In particular, for the main homeland of the main Plant family, the Longspée illegitimate line from Henry II held high office over Staffordshire by 1224, and in 1244 the daughter of the Longspée line married into the Audleys of north Staffordshire. These Audleys also held land in south Staffordshire by 1271 where, moreover, there is also a likely connection to the translation of De Plantis by Alfredus of Sareshel. His apparent birthplace of Sareshel can be tentatively associated with Shareshill near Wolverhampton and, between at least 1167 and 1301, Shareshill and Saredons lay within the royal forest of Cannock in south Staffordshire. The wood at Great Saredons was formed from the royal forest by James de Audley (1220-72) and, in 1271, it was held by his sister Emma. This then renews the possible significance of the philosophical work De Plantis: first, for origins of the Planta name in the Engadine; and then, secondly, for the earliest known evidence of the Plant name in its main homeland of Staffordshire.

The background to the De Plantis translation can be outlined as follows. The first flourish of the Toledo School of translation involved, amongst others, monks from the Order of Cluny though these famed translations went into a transitional stage in 1151, with most of the Toledo gathering returning home, such as to England. A Cluniac priory was established at Dudley in 1160 not far from the evident birthplace of Alfredus at Shareshill who is believed to have translated De Plantis from Arabic to Latin around 1197-1222. As outlined above, De Plantis begins with dismissing Greek teachings of a sensory as well as even an intellectual soul in plants. However, at that time, these new Aristotelian ideas were considered heretical in many parts of Europe, such as in the Condemnations of 1210-77 at the medieval University of Paris. We can hence consider that local discussions concerning the plant soul's powers were still an active topic of controversy, in the Plants' Staffordshire homeland at this late medieval time.

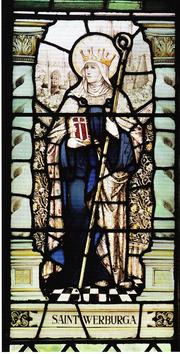

For example, Empedocles' idea that plants had pure souls is suggested also by Henry Bradshaw (d 1513) who wrote in The Life of Saint Werburge of Chester [II 603-7] of the well nurtured plante (soul or unborn child) in Princess Ermenylde...

vertuous doctryne In her so dyd water a pure perfyte plante, Which dayly encreased by sufferaunce devyne, Merveylously growynge in her fresshe an varnaunt,Ermenilda was a princess of the Kentish Royal Legend (11th and 12th century) who married king Wolfram of Mercia (d 675) by whom she gave birth to St Werburgh (d 699), patron saint of Chester. Ermenylde was evidently born at Stone and died at Trentham, both now in Staffordshire. Hence, in this legend for the local Anglo-Saxon royalty, we have a plant growing as more than just a vegetative soul from within a proto-Germanic watery soul. This plant of this vegetative matter was clearly considered to be noble enough to receive the Word of the Lord and thereby to become a Saint. This can be regarded as a continuing vegetative belief, involving the plant of the Word, in the main Plant homeland, borne out also by this homeland's inscription at Wincle Chapel, Here do O Lord sure Plant thy Word.God's plante of St Werburgh and a more worldly vegetative utterance to the head...

[St Werburgh's depiction is in Chester Cathedral and the Green Man is at Leominster in Shropshire. Cheshire is immediately to the north, and Shropshire immediately to the west, of Staffordshire.]

The plante within Princess Erminilda gained sense as a young child ready to receive religious teaching through the Word and, similarly, in the main Plant homeland of Cheshire in 1621 we still have a young man ready for training:

his Grandchild [of Sir John Savage], then a young Plant and newly sent to the Innes of Court, to be trained up answerably to his Birth and Dignity [...] That hopeful Plant, that is the apparent Heir of all his glory and this great DiscentRather as in Plato's Timaeus 77a,77b, this broadly reminds us of a savage or wild plant cultured as a vegetal soul to partake with moderation in societal requirements.

[Mr William Webb's 1621 account of the Hundred of Macclesfield in J.P. Earwaker, East Cheshire: Past and Present (London, 1877), vol. 1, pp. 9-14, esp. p. 10.]Thus, from plants having nous around 500BC, as recalled in references to Anaxagoras, Democritis and Empedocles in De Plantis, we arrive through a tortuous path, around two millennia later, at a conflation of ideas in a pure and perfect plant, watered by virtuous doctrine, to gain the intellect directly created by God.[Roger Bacon, ca.1219-92] We learn from St John's gospel that, In the beginning was the Word... The Word was the real light that gives light to everyone... and there is similar symbolism in the vegetative Green Man heads above uttering less perfectly, it seems, into both the eye of the soul and the head [see Green Man head illustrations above both in this section and as headed 'The vegetative in pain; also, uttering to the eye ...'].

As we explain in more detail elsewhere [J.S.Plant and R.E.Plant (Jan 2017) Royal name Plantagenet concepts, Journal of One Name Studies, 12(9), 11-14], Geffrey Plantagenet was said to have the qualities of an energetic soldier, upright purity, well educated and, through his son Henry, he fathered the so-called Angevin Empire. These self-same qualities are associated in contemporary philosophy with the vegetal soul of plants. With a similar culture carried forward by the Longspées, the Plants can thereby be considered to have been basic souls, to be trained in a tradition of upright purity, as the Longspées saw it, as fathered by their ancestor Geffrey Plantagenet. Whether or not the first Plants fulfilled this requirement, history does not say; and, even if these were the Longspées' requirements, we can be resonably sure that, in troubled times, not everyone would have been fully on their same side.

Around 1200 AD, there is no evidence that the Plant name was known in England. Then, a specific feudal influence under William Longspée, an illegitimate son of Henry II and Ida de Tosnay, apparently developed in England's south and in Staffordshire. William's son, William II Longspée (1212-50) was killed on crusade in Egypt and, around this time, the geographic focus of this feudal influence largely shifts to the Longspée's evidently shared Tosnay origins with the de Staffords in Staffordshire, though Plant records themselves are scant for that early.

During the reign of King John, William Longspée (ca.1176-1226), whose effigy is illustrated to the left, was at court on several important ceremonial occasions and held various offices. In 1210, he was appointed Viceroy of Ireland, jointly with John de Gray, Bishop of Norwich, and was also granted the honour of Eye in Suffolk. He was sheriff of Wiltshire; lieutenant of Gascony; constable of Dover; and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports; and later warden of the Welsh Marches. He was appointed sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire about 1213. After raising the siege of Lincoln with William Marshall he was also appointed High Sheriff of Lincolnshire in addition to his current post as High Sheriff of Somerset. He was appointed High Sheriff of Devon in 1217 and High Sheriff of Staffordshire and Shropshire in 1224. His family inter-married in 1244 with the Audleys who were seated in north Staffordshire.

Longspée meant long sword; the Audley Lords of Staffordshire also were military stalwarts though one died in 1459 leading his Lancastrian army at Bloor Heath in north Staffordshire.

We can consider that the inception of the Plant surname could have developed under this feudal authority in particular. After 1330, in this hypothesis, a salient marriage between the de Audley and de Stafford families evidently widened the cultural rule over the main Plant family fathers.

Before 1350, this apparent context leves some doubt about only the following two known Plant records:

- 1262 Plaunte, Essex (conceivably this also involved an influence similar to Longspée's near his royal relative's English capital);

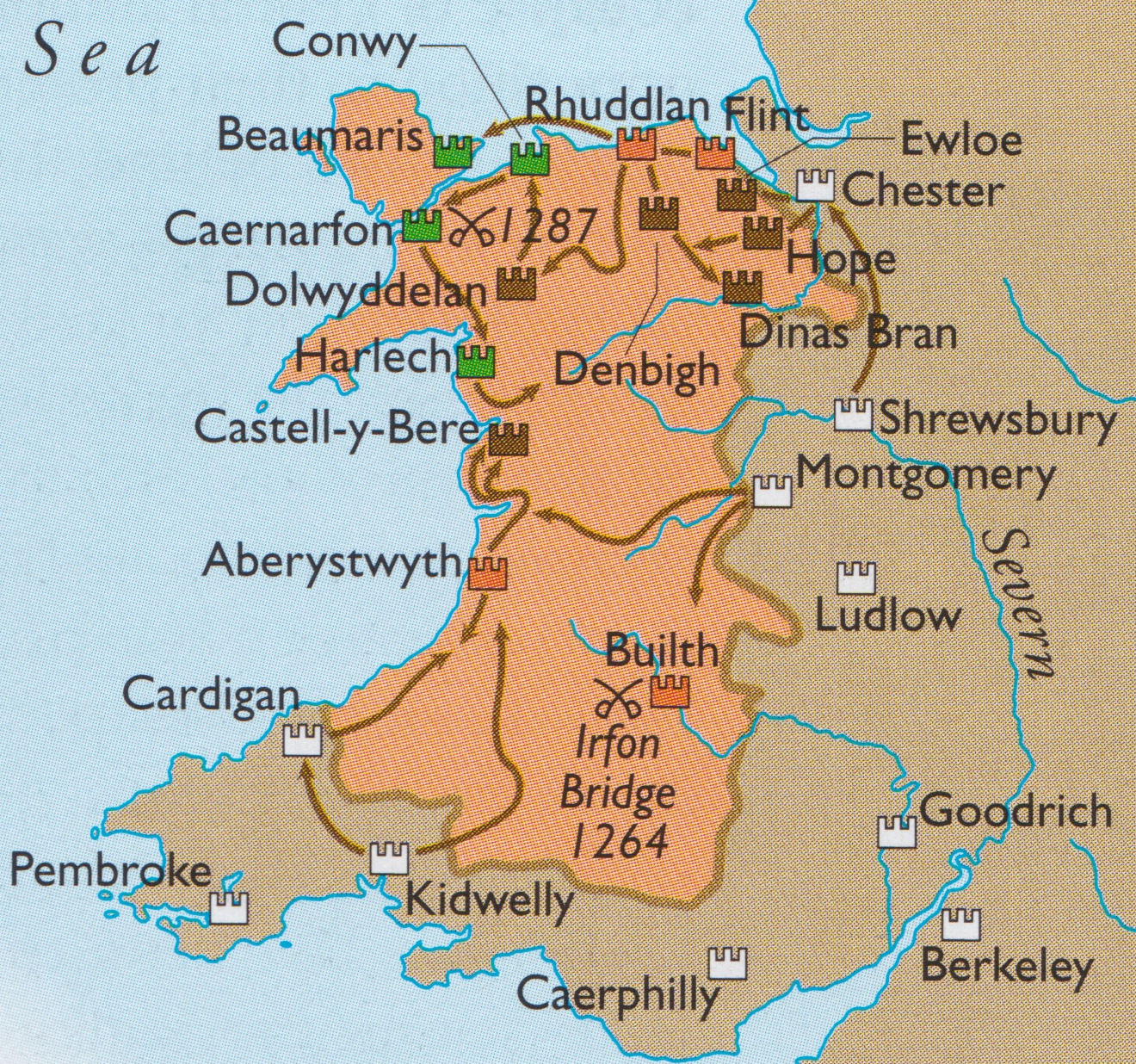

- 1301 Plant, Ewelowe (perhaps a surname remnant from the just-ended Welsh War led by Edward I who set out from Chester; the Audleys' seat was at Heleigh Castle 30 miles away and William de Audley is known to have died fighting the Welsh by 1282; also, Audley lands at Horton were adjacent to Dieulacres Abbey which held lands at Poulton just south of Chester and a few miles from Ewelowe).

Though the following coincident locations sometimes leave a time gap, this is to be expected given the paucity of early records. More detail of the known early records for the Plant name is given elsewhere, here and here, on this website.

The Longspée-Audley context is outlined below with the available known early Plant records interspersed between the numbered items, (1) to (7) outlined in red, in the above diagram.

(1) ca.1176-1226 William Longspée was an illegitimate son of Henry II of England and Ida de Tosnay, Countess of Norfolk. In 1203, he was seneschal of Avranches where his father had done penance for the murder of Thomas Becket. Their families held Normandy and Anjou until 1203. William held various offices: sheriff of Wiltshire; sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire; lieutenant of Gascony; constable of Dover (Kent); and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (Kent); he also held Eye in Suffolk.

(2) 1232 Countess Ela, widow of above William Longspée gives land near (around 3 miles south of) Bath for the relocation of Hinton Priory; the nearby Manor of Charlton still held by the Longspées later. Ela's son Hugh Bigod married Maud, eldest daughter of Willam Marshall, 1st earl of Pembroke whose lands in south Wales reached to the Bristol Channel

- 1180 Durand Plante fined for duelling in the region of Coutances, whose town was just 25 miles from Avranches.

- 1202 Eimeric de Planta (de Plant'), dispossed of land near Anjou after Battle of Mirebeau (possibly killed or taken prisoner)

- 1273 Plaunt and de la Plaunt merchants in Rouen (just across from the Cinque ports in Kent)

- 1279 Plante Cambridgeshire

- 1275 the name Plauntes in Norfolk

- 1282 de Plantes, Huntingdonshire (cf. Rad de Planteiz 1198 in Orne in Normandy, perhaps from the place-name le Plantis in Orne; de Plantes means the same as Plantis means in Latin);

- 1303-1315 Plonte, Canturbury, Kent

- 1350 Plante at Haughley in Suffolk (7 miles from Eye)

- 1352 Plant in north Norfolk

(3) 1244 Ela Longspée (granddaughter of above William and Ela) marries James de Aldithley (Audley) 1220-72, Lord of Heleigh Castle (North Staffordshire), reputedly Ela dies at Heleigh castle in 1299

- 1275-1360 Plonte family near Bath

- 1310 mention of Manor of la Planteland, evidently just across the Bristol Channel in south Wales

(4) Margaret Longspée (ca.1255-1310), dau of above Ela's brother William III Longspée marries Henry de Lacy, whose grandfather John de Lacy had inherited the Barony of Bolingbroke in 1243; Henry's later widow Joan married back into the Audleys, to James de Audley's son Nicholas of Heleigh Castle in 1312.

- 1538-1600 parish records for Plants near Heleigh castle, in Cheshire at Wybunbury (25), and in Staffordshire at Mucklestone (7) and at Audley (6) itself

(5) 1289-1347 Hugh de Audley, Earl of Gloucestershire, (grandson of above James de Audley and nephew of above Nicholas de Audley) was Lord of the Manors of Chilton and Gratton

- 1279 Alan son of Hugh Plante disputes with John son of John Plante over touching land at Burgh (12 miles from Bolingbroke castle). William Marshal had held Burgh in reign of Henry III (reigned 1216-72) and Lady Matilda de Lacy held lands here in the succeeding reign (1272-1307); Margaret's husband, Henry de Lacy (3rd earl of Lincoln) was granted a fair and market at the manor of Wainfleet in 1282 and 1305 (Wainfleet All Saints is 4 miles from Burgh).

(6) ca.1330 Margaret de Audley (only daughter of above Hugh de Audley) abducted by and married by Ralph, who became 1st earl of Stafford in 1350. Their eldest son, Sir Ralph de Stafford (d 1347) married (1344) the child Maud (1340-62), Countess of Leicestershire; she remarried in 1352 and was sister of Blanche who passed on the Lancastrian inheritance to her husband, John of Gaunt. Nicholas Audley (ca.1328-91), the 3rd Baron Audley, married (1345) Elizabeth Beaumont (ca.1320-1400), sister of Isabella of Beaumont, who was the mother of the aforesaid Maud Countess of Leicester and Blanche Duchess of Lancaster.

- 1321 Luke Plonte of Nettlebed, Oxfordshire (17 miles east of Chilton itself)

- 1360 onwards, Plonte at Leek-Macclesfield parishes in main Plant homeland (Leek town itself is 3 miles east of Gratton)

(7) 1357 Katherine de Stafford, daughter of above Margaret de Audley married Sir John de Sutton III (1339-1370 or 76) Master of Dudley Castle.

- 1352 Plaint of Ralph, earl of Stafford concerning James Plant and 30 others taking away goods from ex Warren lands in north Norfolk

- 1373 John Plaint witness to birth of son of John of Gaunt's mistress by her husband (in 1393 document)

- 1376 Will Plante, Leicester Borough Archives

- various Plant documents 1453, 1512, 1537 connected to Beaumont and royal manors near Tur Longton in Leicestershire, also linking (1512) to Merston Culi in Warwickshire

- 1373 Sutton is a common name and it may be just coincidence that John Plaint had been servant of a Master Thomas de Sutton (in 1393 document)

- 1401 John Plonte the younger of Overton (Orton) in Wombourne parish (6 miles from Dudley Castle)

- 1573 Plant at Belbroughton (10 miles south of Dudley Castle)

Some web references....

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/plantagenet_78.html

http://www.cantab.net/users/michael.behrend/repubs/good_glossary/pages/burgh_le_marsh.html

http://www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk/online/content/audley1313.htm

http://www.geni.com/people/Henry-de-Lacy-3rd-Earl-of-Lincoln/6000000004344340204

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hinton_Priory

http://www.geni.com/people/Ela-de-Longesp%C3%A9e-of-Salisbury/6000000002043225943

http://www.geni.com/people/James-de-Aldithley/6000000005935244050

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_de_Audley,_1st_Earl_of_Gloucester

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_de_Audley,_2nd_Baroness_Audley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_de_Stafford,_1st_Earl_of_Stafford

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maud,_Countess_of_Leicester

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol7/pp65-77#h3-0003

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Tosny

Acquisitions of the Audley feudal lords over the Plants

Henry de Audley (ca.1175-1246) was an English Marcher Lord, in command in the Welsh Marches 1223-46. He held for example the castles of Cardigan (1226), Shrewsbury (1233) and Chester (1237) which are all shown in white on the map below. He built for himself castles at Heleigh (NW Staffordshire) and Redcastle (E Shropshire).

His son James de Audley was Lord of Heleigh and he married Ela, daughter of William II Longspée, in 1244. James' son William de Audley (b 18 Oct 1253) succeeded as Lord of Heleigh and died fighting the Welsh before 12 Nov 1282 whereafter his brother, Nicholas de Audley (ca.1258-99) became Lord of Heleigh. This Nicholas married Catherine (b 1272), the daughter of John, 1st Baron Giffard who fought the Welsh at the decisive Battle of Orewin Bridge (1282) and of Maud who was the widow of William III Longspée.

[After the Penguin Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, (Penguin Books, 2005) page 83].

Ewloe castle, near Chester is shown at the top right of the above map. It was built by the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1257 but was captured from the Welsh by Edward I in 1277. It is shown in dark brown along with other Welsh castles that had been captured by 1282-3 – ones in orange were newly begun by Edward 1277-8 and ones in green were begun after Edward's 1282-3 campaign.

Eweloe (in 1301) is also shown at the far left of the map below, which shows some early Plant locations.

By the mid 14th century, the Longspée-Audley family had married into the earls of Stafford and a 1352 complaint by Ralph of Stafford concerned land near Warham [far right of the map above] where the Warren earls had been overlords before the last earl Warren's recent death.

As well as an early Plant record for each of these two far flung places - Eweloe and Warham - there were particularly many Plants in north Staffordshire by the mid 14th century, between Leek and Macclesfield, where the Audleys of Heleigh Castle held land under their overlords, the aforesaid earls of Stafford. There was also an early Plant at Overton near Womburne in south Staffordshire, near where an Audley-Stafford daughter had married into the Dudley lords and where 10 miles north the Audleys had held land at Shareshill and Great Saredon woods in the early 13th century. Furthermore, early Plants were also at Darlaston though, for this placename, there was one possible location near Dudley castle, in south Staffordshire, and also another near Stone further north in Staffordshire, where the Audley family held an estate around 1300 – the evidence of subsequent wills supports the latter location better for the Darlaston Plants.

The developing lands of the Audley Lords had begun broadly as follows — [based partly on Audley: an out of the way, quiet place, published by the Adult Education Department, Keele University, winter classes of 1969-70 and 1970-71, tutor Robert Speake, Chapter 1].

Adam became lord of the manor of Audley in the north west of Staffordshire in the reign of Henry II (1154-89). An early spelling of Audley was Aldithlegh meaning the legh, or pasture fields, of an Anglo-Saxon woman called Aldgyp. The line passed through Adam's grandson Adam to his second son, the aforementioned Henry de Audley (ca.1175-1246).

Shortly before William Longspée (ca.1176-1225) became High Sheriff of Shropshire and Staffordshire in 1224, Henry de Audley was the Under Sheriff (1216-1221), deputising for Ranulf (1170-1223) 6th Earl of Chester and 1st Earl of Lincoln who gave Henry large possessions in the two counties of Stafford and Chester. Shortly after, Henry became the Sheriff of Shropshire and Staffordshire in his own right (1217-20). As well as building Heighley Castle for himself in north west Staffordshire, he acquired royal leave to build another in Shropshire called Redcastle (from the colour of the high rock whereon it was founded).

This Henry de Audley also acquired the Manors of Newport and Edgmond (Shropshire) from the Crown in 1227 and the Manor of Ford (Shropshire) in 1230. Subsequent Plants are evident at Edgmond (1568 will), Sheriffhales (1628 etc wills) 5 miles south of Newport and also at Coton in Staffordshire (1510 document) 4 miles to the east of Newport.

Henry de Audley had acquired much honour as well as estate by founding Hulton Abbey in 1223, being Govenor of the Castles of Camarthan and Cardigan in 1226, being made Constable of the Castles of Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth in 1227, Govenor of Shrewsbury Castle in 1233, Govenor of the Castles of Beeston and Chester in 1237, and then Goveneor of Newcastle-under-Lyme.

This benefited Henry's second son James de Audley (ca.1220-72), Lord of Heleigh, county Stafford who married Ela Longspée in 1244. He was Keeper of the Castle of Newcastle-under-Lyme 1250, Sheriff of Shropshire and Staffordshire in 1261-62 and in 1270-71, fought for King Henry III against the Barons 1264-65, and was Justiciar of Ireland 1270-72.

Feudal Estates in Staffordshire

The estates of the nobility and major gentry were subject to change. For example, the earls of Chester had held important estates in north Staffordshire before the escheat of this earldom to the crown in 1237 which fundamentally changed the local and regional networks of lordly authority, not least for the fee of Leek in the far north of the county of Staffordshire. The north Staffordshire estates of both the Audley [orange squares] and Verdun [blue circles] gentry are shown in map (b) below. The Verduns however were extinct by 1316 and their estates were partitioned except for their Staffordshire estates which passed unchanged to the Furnivals. The estates of the Audley family were more compact, as shown for around 1300 in map (b), with their estates straddling county boundaries – their north Staffordshire estates were matched in Cheshire to the north and in Shropshire to the west.

[An Historical Atlas of Staffordshire, ISBN 978 07190 7706 7 hardback, pages 54-55]As outlined above, in the section describing evidence for the Longspée-Audley feudal hypothesis, Audley females married with the Staffords ca.1330 and then with a Dudley lord in 1357. This openned up the possibility of a subset of secondary connections to much of central Staffordshire [red triangles] and south Staffordshire [blue squares], as indicated in map (a) above. Perhaps also affecting the distribution of the early Plant name, a link to Leicestershire county, to the east of south Staffordshire, arose with the 3rd Baron Audley's 1345 childless marriage to Elizabeth Beaumont (ca.1320-1400), who was an aunt of Maud (1340-62) Countess of Leicestershire and Blanche (ca.1346-68) the first wife of John of Gaunt.

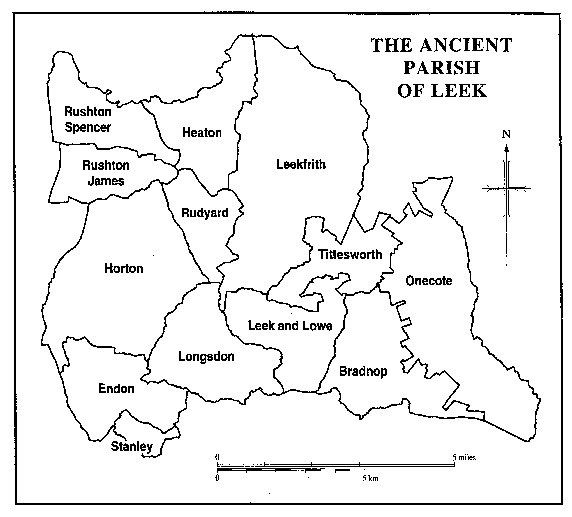

ClickThe parish of Leek

Plants are known to have been in their Leek-Macclesfield homeland from ca.1360 and could have been there much earlier. Leek had been granted to Hugh, earl of Chester by 1093 who had succeeded his father to the title of Vicomte d'Avranches in 1082 with parts of Leek granted to Henry de Audley in 1218.

Before the Conquest Leek belonged to the earl of Mercia, while thegns held Endon, Rudyard, and Rushton. All were held by the Crown in 1086, but by 1093 Leek had been granted to Hugh, earl of Chester. The entry in Domesday Book for Leek 'with the appendages' probably covered the site of the later town, Lowe to the south and west, Tittesworth, the area of the later townships of Bradnop and Onecote, and most of Leekfrith. Bradnop and Onecote became separated from the rest apparently in the 12th century, and in 1218 manorial rights within that area were granted to Henry de Audley. The rest of the Domesday manor of Leek was enlarged to include part of Rudyard manor (the south-west part of the later Leekfrith township and probably Heaton township), and the northern half of Rushton manor (the later Rushton Spencer). As a result Leek manor comprised the tithings of Heaton, Leekfrith, Lowe, Rushton Spencer, and Tittesworth. The core of Rudyard manor remained separate. The southern half of Rushton manor (later Rushton James) became part of the manor of Horton, created by the Audley family and including Horton itself, Endon, Longsdon, and Stanley together with Bagnall, in the parish of Stoke-upon-Trent.

Early modern Plant records (1532-2) are found particularly in LEEKFRITH as well as LONGSDON and BRADNOP aswell as at Leek (presumably Leek town in the LEEK AND LOWE quarter). The medieval Audleys had held HORTON and, in particular, the manor of Gratton. Gratton is now 3 miles west of Leek town. To the north of the parish was the quarter of HEATON immediately to the south of the first known precise location for a Plant in their main homeland, at the Black Prince's vaccary in 1373 just over the border into Cheshire. Less precise records for Plants near here, over the Cheshire border, are available from the first appearance of adequate records in 1360. Dieulacres Abbey was near Leek town (see map here) and there are some early connections between the first known Plants in this main Staffordshire-Cheshire homeland and this Abbey. After the Abbey's dissolution, William Plant of Heaton bought half a share of HEATON in 1614 and sold it in 1631. For early modern parish records, see also pages 22-26 of http://plant-fhg.org.uk/articles/plshef2b5.pdf

Early modern division of Leek parish by 1609 and probably by 1553...

The following are extracts taken directly from the Victoria County History of Staffordshire concerning Leek parish.

About 1140 Robert de Stafford gave HORTON with Gratton to Stone priory, of which he was patron. (fn. 76) His grant was ultimately ineffective. The Staffords remained overlords, and in 1276 the Audleys held Horton of them in socage, paying a rent of 10s. (fn. 77) The overlordship descended in the Stafford family at least until 1408, when it was held by the earl of Stafford. (fn. 78)

Ralph son of Orm was the tenant in the later 12th century. He was succeeded by his daughter Emma, the wife of Adam de Audley. Their son Adam (d. by 1211) was succeeded by his brother Henry de Audley. (fn. 79) In 1227 Henry successfully held the manor against Hervey de Stafford. After a judicial duel Hervey acknowledged Henry's right to Horton in return for a payment of 50 marks and land in Norton-in-the-Moors. (fn. 80) Henry, sheriff of Staffordshire and Shropshire 1227-32, was succeeded in 1246 by his son James (d. 1272). Four of James's sons succeeded in turn, three of them dying childless: James (d. 1273), Henry (d. 1276), William (d. 1282), and Nicholas (d. 1299). Nicholas's son and heir Thomas was succeeded in 1307 by his brother Nicholas, from 1313 Baron Audley. Horton then descended with the barony until the death of Nicholas, Lord Audley, without issue in 1391, when the manor was divided into three parts. One share passed to his sister Margaret and her husband Sir Roger Hillary; another to John Tuchet, later Lord Audley, grandson of Nicholas's sister Joan; and the third to Fulk FitzWarin, grandson of Nicholas's half-sister, also called Margaret. (fn. 81) On Margaret Hillary's death in 1411 her share passed to James, Lord Audley, the son of John Tuchet. (fn. 82) That two-thirds share descended with the Audley barony until 1535, when John, Lord Audley, gave it with other estates to the Crown to pay off his debts. (fn. 83) The FitzWarin share remained with Fulk's descendants, earls of Bath from 1536. (fn. 84)

The manor of FRITH was first mentioned in 1552 when the Crown granted what were described as the manors of Leek and Frith with the site of Dieulacres abbey to Sir Ralph Bagnall. Frith manor descended with Leek manor. (fn. 92)

What became the manor of HEATON was probably included in the grant of Leek manor by Ranulph, earl of Chester, to Dieulacres abbey in 1232. (fn. 42) The abbey had granges at Fairboroughs and Swythamley by 1291, and in 1535 it held what was called the manor of Heaton. (fn. 43) After the Dissolution the Crown retained the manor until 1614 when it was sold to William Tunnicliffe of Bearda Farm and William Plant, also of Heaton. They sold it in 1629 to George Thorley of Heaton, from whom it was bought in 1631 by Francis Gibson of Wormhough.

Extracts mentioning Plant from the 1883 edition of A History of the Ancient Parish of Leek (supplied by Prof Richard Plant)

- page 8: inn holders: 1564, Feb. 24. (Late) Nicolas Plounte of ye Swanne, now in the occupation of Nicolas Mountgomere, gen.

- page 38: John Plant's deed of Stonycliffe (Saultersclough?)

- page 51: 1406. Lease for thirty-nines year from abbot and convent of Dieulacres to Edward Plont of two mess' ... with one croft call le Calwo-heye de Roche-graunge ...

- page 69: Fees and annuities granted out by Convent seal, before the dissolution of Dieulacres Abbey in 1539: Laurence Plaunte, xx s

- page 71: Dieulacres rent-roll in 1543:

- Frythe: Reginald and Laurence Plont for Rederth 53/4: Wm. Plont, for the Brendock-Holins, 13/8, do. for the 4th pt. Hulme mylne, 5/-: Helena Plont, for the 4th pt. of Hulme mylne, 5/-

- Tetisworth: Richd. Plont, for a yate over rivulet running between Tetisworth and lordship of Bradnapp, 4d: Henry Plont, 21/8: Wm Plont, 12/-: Helena Plont, 8/-

- Lowe: Robt. Plont, 15/-

- page 113: Pedigree of Hulme: 1696: James Hulme, 2nd son = Mary, d. Plant, of Alstonfield; M.S.

- page 114: ... giving Richard Plant, of Stonscliffe, leave to make an enclosure (clausuram) near a place called Lingrene in Henry 6th's time ...

- Pedigree of Brough: William Brough, of Middle-Hulme, n 1725, ob 1755 = Mary, d of William Plant, of Stoney Cliff, Leek.

- page 120: 2 Feb 7th Elizabeth, St Matthew Chapel trustee granted to Thomas Holme in presence of 8 men including Robert Plaunt

- page 126: 1504: Raufe Rydrort, gentylman, hath boght of Lawrence Plont of the Reede-yerth a tent etc ...

- page 189: subsidy roll mentions Plonte: 26th Jan 5th Edward 6th Leek Laurencio Plounte 10s

- page 215-6: 1801: One Plant, who Mellar says, gave him the note for which he was convicted, and also the sister of Fearnes before-mentioned, go about on horseback passing forged notes and base coin. ... William Plant ... lives at a place called Irwin's Hall, in the parish of Warslow, near Longnor, in Staffordshire ...

- page 218-9: 1395: witness to deed in Leek, John Plonte